Unity or deeper divisions among us?

The energy of the last days, in which people believe they must take a position for or against Bishop Budde’s sermon, runs contrary to what the bishop asked of us in the first part of her sermon. The climate is a bit like the 1950s with people being asked to sign loyalty oaths and to assure us that they were not Communists. Though, so far, that pressure is more tribal than government action is.

All the emotional energy and pressure is around her final words, materials that she has said came to her at the last minute. We wonder if we might all benefit by listening instead to just the first segment of the sermon, when she suggests that we have gathered “to pray for unity.”

“To pray for unity…not for agreement.” She went on to speak about the necessity of unity for people to live in a free society. “It is not conformity. It is not victory…Unity is not partisan.” “…unity is a way of being with one another that encompasses and respects our differences, that teaches us to hold multiple perspectives in life experiences as valid and worthy of respect.” She continued to speak about the capacity to care for one another, even when we disagree. “Unity at times is sacrificial in the way that love is sacrificial.” We are “to love, not only our neighbors, but also our enemies.” She spoke of this as being something that was worthy of our best and who we could be. She expressed concern about how we might “deepen the divisions among us.”

We suggest that much of our behavior in recent days has been just what she cautioned against – acting in ways that “deepen the divisions among us.” There has been significant pressure on bishops and priests, and on parishioners, to approve or disapprove of what amounts to the last section of the sermon. Many aren’t even aware that the part they’re so focused on is just that—a part.

“We fell morally ill”

Douglas Murray, in his weekly Free Press newsletter, “Things Worth Remembering,” wrote about Václav Havel, who became President of Czechoslovakia after the Velvet Revolution in 1989:

“The worst thing is that we live in a contaminated moral environment,” Havel said in his 1990 address. “We fell morally ill because we became used to saying something different from what we thought. We learned not to believe in anything, to ignore one another, to care only about ourselves.”

The most devastating effect of this contamination, Havel explained, is a melting away of real emotions and relationships—a grotesque atomization that leaves us feeling deeply alone, misunderstood, frightened.

“Concepts such as love, friendship, compassion, humility or forgiveness lost their depth and dimension, and for many of us they represented only psychological peculiarities, or they resembled gone-astray greetings from ancient times, a little ridiculous in the era of computers and spaceships,” he added.

Does that feel at all familiar to you? If you voted for Donald Trump, have you found yourself in situation where you have self-censored, where you stifle your doubts or disagreements? And are you one of the many progressives who struggle to find the courage to self-differentiate yourself from the list of “approved” positions on cultural issues?

Is it all getting worse? Or maybe things are turning toward a more open conversation. We don’t know, and neither do you. The recent trends have had us literally moving away from one another into states and religious groups that align with our political views.

The Drama Triangle

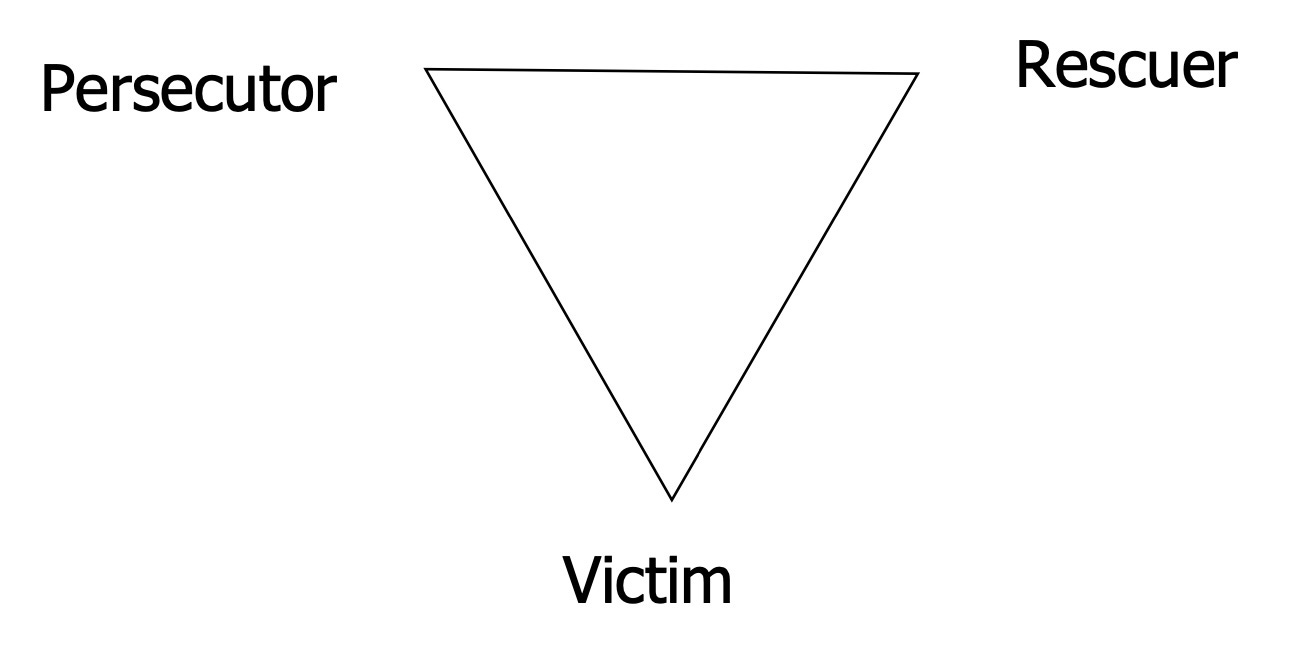

There’s a useful concept in both family systems theory and group dynamics called the Drama Triangle. It was developed by psychiatrist Stephen Karpman in the ’60s and describes a destructive tendency to assume one of three roles when interacting with others: persecutor, victim, or rescuer. The Wikipedia entry[1] on the subject says, “Karpman described how in some cases these roles were not undertaken in an honest manner to resolve the presenting problem, but rather were used fluidly and switched between by the actors in a way that achieved unconscious goals and agendas. The outcome in such cases was that the actors would be left feeling justified and entrenched, but there would often be little or no change to the presenting problem, and other more fundamental problems giving rise to the situation remaining unaddressed.”

The tricky part is that we don’t undo the damage of the Drama Triangle by assuming a different role. Shifting from persecutor to rescuer, for example, just continues the drama. We start to improve things by stepping out of those very limited roles. By self-defining—what do I care about? What do I need? What do I hope for? And also by practicing empathy. By creating space for the values, needs, and hopes of others but not primarily trying to define or impose them. The assumption is that we are inter-dependent and need to be both unique individuals and in meaningful relationship with other unique individuals. This reminds us of theologian John Macquarrie’s view that, “The end, we have seen reason to believe, is would be a commonwealth of free, responsible beings united in love; and this great end is possible only if finite existents are preserved in some kind of individual identity.”[2]

There have been comments in various outlets in response to reporting on this issue. We have made up a few examples of the kind of statements that have been posted. How would you characterize the speakers in light of the Drama Triangle roles?

I want to thank Bishop Budde. All our clergy need to show that kind of courage. Speak up in the face of the Trump’s evil. The bishop was compassionate and spoke the truth. She wasn’t nasty or aggressive. The clergy who support Trump are crucifying Jesus and all he taught Such hypocrisy!

It was a disgusting sermon offered by a bishop —proclaiming false fears and ignoring real fear. She demonized measures being taken for our protection, falsely claiming they were good.

The Bishop was speaking in defense of the exploited. And some think she was speaking out of school about things she had no right to address. That man embarrasses himself every day. She wasn’t shaming him. It was an appeal to his humanity.

This was grandstanding and grandstanding is pride. If she had a deep desire to ask the president be merciful, she could have had a private word with him or sent a letter. But if she did something so humble we would not have seen her courage and virtue.

My family watched the entire sermon. It was about unity and compassion. We noted that she showed her political leanings in the last segment. That was a bit uncomfortable. But “showing mercy” wasn’t telling him any specific action he should take.

As you read these comments, think about your own tendency to defend (rescue), to attack (persecute), or to identify with the one you see as the victim.

It’s not too late

Our hope is that in some parishes and dioceses the complete sermon is used to have conversations that nurture unity and humility. It’s really not too late for that to happen. In many places we’d have to stop ourselves and acknowledge that we have gone down a road that is not congruent with the fullness of the bishop’s words or the Gospel. Rather, we jumped into exactly the division she cautioned us against.

What might that conversation look like?

We think there are probably dozens of paths into unity. Here’s one that occurs to us.

Have a conversation about mercy and justice. Maybe add in a bit about grace.

Mercy suggests that there has been a real offense and, rather than exacting the full measure of punishment for the offense, we instead offer something kinder and less harsh. Grace, on the other hand, implies a freely given act of love. Something given that we don’t deserve, provided by God or our neighbor.

Justice has two primary meanings. One is connected to the inherent purpose of government[3] involving the encouragement of good behavior and the punishment of bad behavior; to take action so “we may lead a peaceful and quiet life.” And a second meaning having to do with creating a just society.[4] Yes, they are intertwined.

We might then go further and explore our various views in a manner that “encompasses and respects our differences, that teaches us to hold multiple perspectives in life experiences as valid and worthy of respect.” As just one example, we might discuss immigration.

Justice: Some people who came as immigrants by following all the laws see it as unjust that people who broke those rules are allowed to enter and remain. Others think we will create a fairer and more just society by offer grace to all who wish to enter the country.

Mercy: Many want mercy for all those who came as children even if their parents broke the law by coming. Others want justice regarding those who entered illegally and have some criminal association.

And what about the end of the sermon? We did suggest considering the “complete” sermon, and the end is clearly the part where most of the energy has come from, and it’s the part that most are talking about when they line up for or against it. After reflecting on the broader message of unity and undertaking an exploration like that described above, you might also think about the end more broadly.

Those who support the President might, after considering the rest of the sermon, ask why the Bishop felt compelled to address a particular member of the congregation—and not just a member, but the President of the United States, arguably the most powerful person in the world—as she did. Can you imagine reasons that come from a better place than partisan politics? Is there possibly something of value in what she was trying to do, even if it didn’t work? How does her summary of the policies at stake point to deeper underlying values you might agree with—or at least appreciate—while also clarifying how she might misunderstand the impact or have inaccurate assumptions?

And those who do not support the President might also look more curiously at the end. It’s certainly not the norm in an Episcopal church to preach at any one person. Many of us have an intuitive understanding that doing so is unlikely to lead to much good. And what about the policy issues she raises? As the above exploration of immigration illustrates, it’s extremely difficult at any time to provide a nuanced summary of complex policies in a sermon. That’s especially true when the summary seems to have been added later, leaving less time to finesse it. Any summary is likely to leave out considerations that supporters believe are critical to understanding. Can you imagine that supporters of the President would feel personally attacked, not only because their politics are apparently (and to them, unfairly) deemed deficient, but because they are possibly being characterized as unchristian as a direct consequence of those politics?

We would suggest there is value in understanding why both sides see the end as the most important part. We also think there is value in assuming that’s the most important part to let go of. Doing so requires forgiveness and humility, and recognizing that none of us gets everything right.

In all of this, the task would be to listen with respect to one another. And as your group isn’t the Congress, there’s no need to argue and try to convince one another that your views are correct and theirs wrong. To paraphrase the bishop, the aim is to pray and discuss, seeking unity, not agreement.

We love that today is the feast of Thomas Aquinas - a theologian seen as so pedantic and "right." The bio in the Brotherhood of St Gregory app had this:

In December 1273, after decades of churning out theological writings at an astonishing pace, Thomas suddenly stopped, leaving his great Summa unfinished. When pressed as to why, he could only say that he had experienced a mystical encounter so profound that all of his former words seemed empty to him now. "All that I have written seems to me like so much straw compared to what I have seen and what has been revealed to me!"

This abides,

Sister Michelle, OA & Brother Robert, OA

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karpman_drama_triangle. Retrieved January 28, 2025.

[2] John Macquarrie, Principles of Christian Theology, 2nd ed. Pearson Publishing.

[3] “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God. Therefore whoever resists authority resists what God has appointed, and those who resist will incur judgement. For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Do you wish to have no fear of the authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive its approval; for it is God’s servant for your good. But if you do what is wrong, you should be afraid, for the authority does not bear the sword in vain! It is the servant of God to execute wrath on the wrongdoer. Therefore one must be subject, not only because of wrath but also because of conscience. (Romans 13:1-5) and “First of all, then, I urge that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for all people, for kings and all who are in high positions, that we may lead a peaceful and quiet life, godly and dignified in every way.” (1 Timothy 2:1-2) and "For the Lord’s sake accept the authority of every human institution, whether of the emperor as supreme, or of governors, as sent by him to punish those who do wrong and to praise those who do right. For it is God’s will that by doing right you should silence the ignorance of the foolish. As servants of God, live as free people, yet do not use your freedom as a pretext for evil. Honor everyone. Love the family of believers. Fear God. Honor the emperor. (I Peter 2: 13-17) And of course there’s much more, including Revelations 21 with its caution about the beast.

[4] “learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow.” (Isaiah 1:17); “Give justice to the weak and the orphan; maintain the right of the lowly and the destitute. Rescue the weak and the needy; deliver them from the hand of the wicked.” (Psalm 82:3-4); “I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strayed, and I will bind up the injured, and I will strengthen the weak, and the fat and the strong I will destroy. I will feed them in justice.” (Ezekiel 34:16); “Cursed be anyone who perverts the justice due to the sojourner, the fatherless, and the widow.” (Deuteronomy 27:19)