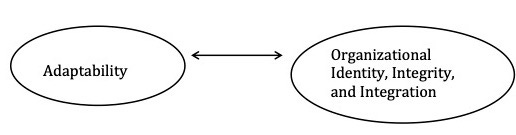

Adaptability and Integrity, identity, integration

The work of every parish church and program

O God of truth and peace, who raised up your servant Richard Hooker in a day of bitter controversy to defend with sound reasoning and great charity the catholic and reformed religion: Grant that we may maintain that middle way, not as a compromise for the sake of peace, but as a comprehension for the sake of truth; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.

Maintaining the boundaries of your parish or program culture

When Robert was Vicar of a parish in Trenton, New Jersey, a woman started to come to the 10:00 am Mass. She was much more politically and theologically conservative than most others in the congregation. That, in itself, was fine. She was welcome to be part of the congregation. However, at one point she came to Robert and said she was very uncomfortable because Allan and Ed held hands during the service and kissed each other at the Peace. He listened and acknowledged this was different from what she had experienced in other parishes. And then he told her that it wasn’t going to change. It was simply an expression of how the Christian life was expressed in that parish. About a month later, she left the parish.

The two of us have conducted a variety of parish development training programs over the decades. We’ve had people complain because we were too liberal or too conservative; because we used the United States Marine Corps as an example of a successful dense culture; because we share material from writers in ascetical theology and organization development who didn’t use inclusive language; because we allocate more time to small group application than to trainer presentations; because we use a number of organization development theories that are more than 50 years old; because we insisted on using Prayer Book norms in saying the Psalms in the Daily Office. We didn’t change our approach on any of those issues. Most of the people raising them stayed in the program, and some left.

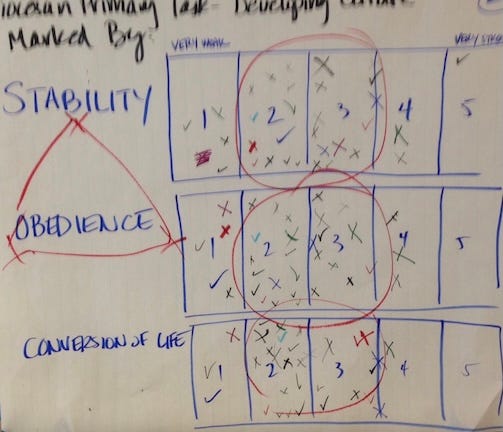

The Benedictine Promise

The Benedictine Promise of stability, obedience, and conversion of life are expressed in various ways depending on the setting. A Benedictine monastic community will look on stability as binding a monk for life to the monastery where he professed the Promise. In dispersed Benedictine communities it may have more to do with a stability of relationships and disciplines of worship and prayer. Esther de Waal saw it this way: “Stability brings us from a feeling of alienation, perhaps from the escape into fantasy and daydreaming, into the state of reality. It will not allow us to evade the inner truth of whatever it is that we have to do, however dreary and boring and apparently unfruitful that may seem.”[1]

We once had a young priest upset about the very idea that stability was understood as something good. He thought that the faith was only about change.

Saint Benedict lived and wrote his Rule in the 5th and 6th centuries. The Benedictine promise appears in chapter 58 of the Rule. “When he is to be received, he comes before the whole community in the auditory and promises, stability, fidelity to monastic life, and obedience.”[2]

Over the centuries societies have had periods where change and conversion were looked upon favorably or unfavorably, stability was looked upon favorably or unfavorably, the very word obedience was looked upon favorably or unfavorably. And here we are in the 21st century, and men and women still commit themselves to the ancient Promise. Over the long-term, the wisdom of the Promise has reasserted itself again and again against the cultural and political fads of the moment.

We have used the Promise to help a diocese articulate a spiritual difficulty it was facing, to help parishes understand more of the internal logic of Anglicanism and therefore their identity, and in our own lives to ground and orient ourselves.

For stability means that I must not run away from where my battles are being fought, that I have to stand still where the real issues have to be faced. Obedience compels me to re-enact in my own life that submission of Christ himself, even though it may lead to suffering and death, and conversatio, openness, means that I must be ready to pick myself up, and start .all over again in a pattern of growth which will not end until the day of my final dying. And all the time the journey is based on that Gospel paradox of losing life and finding it. ..my goal is Christ. Esther de Waal in Seeking God: The Way of St. Benedict

All systems have a culture and therefore a leaning (a bias)

All parishes and programs have a tilt, a leaning of some sort. We think there’s a lot of value in understanding who you are at your best, embracing it, and building on and deepening that. That does, though, require recognizing that who you are may not be to everyone’s liking.

The parish we attend is Anglo-Catholic with an African American heritage. Some of that is rather visible – incense most Sundays, two Religious in a front pew, and icons of Anglo-Catholic saints ranging from John Henry Newman and Mother Harriet Monsell, to the Martyrs of Memphis and Bernard Mizeki, to Jon Daniels and Frances Perkins. You need to hang around for a few months before you’ll see another very visible aspect of our culture. Several times a year we have community meetings in which parishioners gather to assess and reflect on our life together. The less visible aspects of the parishes culture will come to the new member bit by bit. For example, love of one another outweighs a desire for agreement on political and cultural issues (“love wins” says the rector) and there is a climate of acceptance (“Give people some slack,” “forgive,” “show mercy,” “you are an instrument of God’s love to the world”).

The Shaping the Parish program we lead rises out of a mix of the Broad Church tradition of pastoral theology and the use of the behavioral sciences, and the Catholic emphasis on ascetical theology and practice. Participants who come from a more evangelical tradition may find us lacking in that regard. Those with a background in the Broad Church or Anglo-Catholic traditions that stress political and cultural struggles for justice may be disappointed.

All parishes have boundaries

We use the concept of inclusion as an illustration. Going back to the illustration that opened this post, in Robert’s Trenton parish a gay couple holding hands was easily within the bounds of inclusion in that parish culture, whereas the woman seeking to restrict that behavior experienced a lack of inclusion.

If someone stood up during announcements at our current parish and said, “I find the use of incense upsetting and offensive. I would like to have a discussion about that now,” the likely response from the rector might be, “We do have one Sunday each month without incense and I’d be glad to talk with you after Mass, but this is not the appropriate time.” If it turned out that the person simply could not tolerate being in a parish using incense, we would not be able to include them in our life other than that one Sunday a month. That’s connected with preserving the parish’s identity and integrity as an Anglo-Catholic parish, and the person who doesn’t like incense may feel hurt or excluded or disappointed. Another way to say it is that adequate attention to the kind of inclusion that serves a system’s purpose and common life always involves some form of exclusion. That’s the nature of boundaries.

Inclusion

There are people in the Episcopal Church who would define a healthy and faithful parish as one that spent considerable energy on the inclusion of populations that are frequently marginalized. Many people would experience our parish as pretty inclusive in that sense, though you would not get the impression in the community that we are engaged in some kind of cause. It’s simply how we live. Our inclusion problems would have to do with people who were more politically conservative and families with young children.

In recent years, the larger church’s concern about “inclusion” appears to have replaced “growth” or “evangelization.” Go back 20 years and the church’s concerns for membership growth and increasing the average Sunday attendance were more prominent than the inclusion of marginalized populations, though that was beginning to be picked up as an interest. When the Episcopal Church began to decline in membership back in the 60’s there was a sociology orientation that noted how parishes growing tend to be homogeneous. The general human desire to be around people like ourselves still holds sway. Only now it is less about race and class and more about political and cultural beliefs. In either case, the term “inclusion” is used to look at who is “in” and who is “out.” It has a political and culture war meaning for many on the right and the left.

In the Shaping the Parish program we don’t look at that form of inclusion at all. Our emphasis is on understanding inclusion as a phase in group or organization development. For example, one theory suggests that systems need a degree of inclusion that allows them to effectively deal with people’s need for control and influence, which in turn affects the openness and affection present in the community.

People who would like us to address parish development through a current political or cultural trend are likely to find us lacking. There’s a whole political battle going on around the word inclusion. Our parish development program is not engaged in that political battle. We are engaged in using behavioral science theory to strengthen the internal commitment and level of collaboration within parish churches. Our concern is to help parish leaders understand the dynamics of group and organization development. So, our approach to inclusion and acceptance would look at how much people in the parish community accept others in the community as belonging and having something to contribute to their life together. And as real inclusion is a two-way street, the new person must make an effort to include themselves and accept the ways of this parish. We must make ourselves at home. To the extent that happens, there may be a free flow of communication among people, which can lead to a higher degree of agreement about a parish’s direction. Inclusion is simply a step that is followed by other steps.

Maintaining the system’s culture

The oversight of parishes and programs calls upon leaders to nurture a healthy, faithful, and dense culture. As much as may be possible given the circumstances of the parish or program. One aspect of that task is to keep the focus of our time and energy on the stated purposes of the parish or program. So, the hypothetical example of the person wanting to have a discussion about incense at announcements during the Eucharist and being told by the rector that they could talk about it later (and, of course, not actually allowing that person to unilaterally affect a key part of the parish’s liturgical practice)—that’s an example of a leader protecting the time, energy, and integrity of the community. The rector would be stopping an attempt to interfere with the focus of that gathering, as well as a way of interacting that doesn’t fit the parish’s broader culture.

We take the same approach in the Shaping the Parish program. When a participant in a small group turns the conversation to current politics instead of the assigned educational task, we will speak to the person and ask them to help the group stay with this work as a learning community. The world is full of spaces totally devoted to political and cultural issues. Above we noted the program’s roots in the Broad Church tradition of pastoral theology and the behavioral sciences, and the Catholic emphasis on ascetical theology and practice. Our agreement with participants is that their time in the program, as well as ours, will be given to how to use the knowledge and skills offered in the program. We won’t spend the group’s time debating the program’s orientation or the use of particular models and theories. If a participant would like an exchange about that, we are often glad to do that outside of the sessions by email or possibly in a Zoom conversation. That might help a participant settle in and learn what they can from this program, even though they might wish we were giving more attention to something they were interested in. On the other hand, it might clarify the need for the person to seek another program.

Part of organization development is “finding ways to adapt to the changing context while maintaining and enhancing the organization’s integrity and internal integration.”[3] In the parish, that means ensuring that primary things remain primary, and also ensuring there are adequate listening processes in place so that the parish can identify issues—both internal and external—and respond to to them faithfully. Over time, we will change how we do things. In some cases, we will change very quickly. Once beloved practices will morph or maybe even be abandoned. Something we cared deeply about may come to be seen as harmful. In all of that, the Benedictine roots supporting much of Episcopal parish life function best with the understanding that change—conversion of life—emerges from our stability—especially in prayer, worship, and commitment to common life--and our obedience, or listening, to God, ourselves, the wider church, and the external environment.

Parts of the church always live and order their lives to conform to the moment. Historically, as part of the Broad church tradition. The moment may be a movement that gains traction and sweeps across a society within a few years. Or maybe something that builds over time and carries on for decades. Many of us have been caught up in the cultural and political trends of the last three years or two decades. Some have found themselves significantly shaped by progressive or right-wing politics. It becomes a primary lens through which they look at things and make sense of the world.

Our parish development approach doesn’t work that way. We seek ways of understanding systems, rooted in organization development, organizational psychology, and ascetical theology and practice. We believe that the knowledge and skills of those disciplines have a longer shelf life.

A bit of patience, a bit of persistence.

If you’ve come to a parish to be fed and grow, you’ll find yourself needing to decide whether this parish’s way of doing that has an adequate alignment with your temperament and circumstances. And it may take some time before you see how that will unfold for you in that particular parish.

Similarly, if you came to Shaping the Parish to learn the knowledge and skills it offers, you need to give it a chance. We don’t mean just intellectually for a few minutes as you run things through your existing filters of what you believe to be the best parish life. As with a parish church, we’d hope you’d sit with it for several months, try out the processes and skills several times, reflect upon your experience, work at understanding the perception of others on how all this works in their parish and how that differs from your parish.

On occasion, we have participants in a parish development program seeking an approach that exactly fits their particular parish. They may say, “Why do I need to understand how other parishes function differently or have dynamics and lives that are effective but different from my parish?” Our general answer will be, “Because three years from now your parish is likely to be different than it is now. Maybe not dramatically but to some extent. The dynamics in a parish change over time. And if you keep thinking that they haven’t changed or they will never change, you’re going to miss it.”

God is no captious sophister, eager to trip us up whenever we say amiss, but a courteous tutor, ready to amend what, in our weakness or our ignorance, we say ill, and to make the most of what we say aright. (James Kiefer’s recollection of the words of Richard Hooker)

This abides,

Sister Michelle, OA & Brother Robert, OA

[1] Esther de Waal, Seeking God: The Way of St. Benedict

[2] In other translations you may find something like this, “Let him who is received promise in the oratory, in the presence of all, before God and His saints, stability, the conversion of morals, and obedience.”

[3] Robert A. Gallagher, 1987, from material used in the Church Development Institute’s training manual.

The Feasts of All Souls / All Faithful Departed (Tr) and Richard Hooker, Priest & Theologian, 1600